The Storied Saga of the 71st Ohio Volunteer Infantry

The Storied Saga of the 71st Ohio Volunteer Infantry

Upon an initial review, the 71st Ohio Volunteer Infantry (OVI) may seem like a regiment that was on the sidelines of the the American Civil War. However, upon a deeper dive, their story is as turbulent and fascinating as many of the more active regiments that may have had more of a combat role.

Formed in late 1861 in western Ohio, this regiment’s journey spans early battlefield controversy, years of garrison duty, and a hard-won redemption in the war’s final campaigns. Along the way, its soldiers left behind letters and records rich with personal stories – from tales of cowardice and courage at Shiloh to daily ledger entries now preserved in newly digitized regimental books. This post provides an informative yet entertaining chronicle of the 71st Ohio Infantry’s service. We’ll explore the regiment’s formation, key engagements, commanders, and notable anecdotes. We’ll also spotlight the Research Arsenal’s recent digitization of the 71st Ohio Volunteer Infantry’s regimental ledgers – including descriptive rolls, morning reports, and order books – explaining what each contains and how they bring the soldiers’ experiences to life for modern researchers.

Formation of the 71st Ohio Volunteer Infantry: “Camp Tod” and Early Struggles

The 71st Ohio Volunteer Infantry began organizing in September 1861 at Camp Tod in Troy, Ohio, as the nation realized the Civil War would not be a short conflict(source). Recruiting largely drew men from Miami, Mercer, Auglaize, and Clark counties of western Ohio. Like many volunteer regiments of 1861, local politicians and prominent citizens played a major role in raising companies – and often secured officers’ commissions as a reward. In the case of the 71st OVI, Rodney Mason, the son of a well-known Springfield politician (Samson Mason), leveraged his connections to be appointed colonel, surpassing Lt. Col. Barton S. Kyle who had done much of the organizing work. This caused some grumbling in the ranks, as many soldiers respected Kyle and resented Mason’s political ascent. Nonetheless, the men’s admiration for Kyle kept them united, and the regiment mustered into Federal service for three years on February 1, 1862.

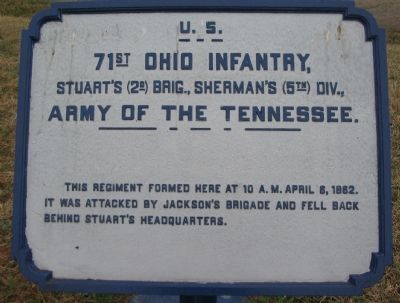

Armed initially with antiquated Belgian muskets, the 71st Ohio traveled to the Western theater of war. After a grand send-off dinner in Piqua, they paraded in Cincinnati and then moved to Paducah, Kentucky in February 1862. There they encountered the grim realities of war for the first time – seeing wounded from Fort Donelson with missing limbs and ghastly injuries, a sight one private described as “an awful sight to see… cut up in every way”. The regiment was assigned to the Army of the Tennessee, in Colonel David Stuart’s brigade of General William T. Sherman’s division.

Trial by Fire at Shiloh: Controversy and Courage

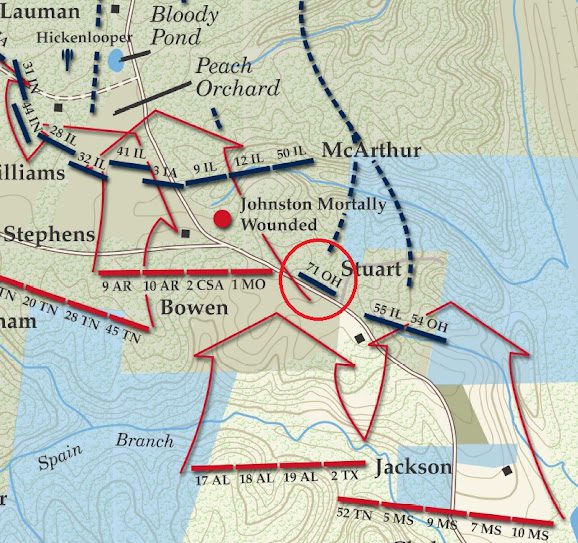

The 71st Ohio’s first major combat came at the Battle of Shiloh (Pittsburg Landing) on April 6–7, 1862 – and it would brand the unit with infamy and debate. The regiment, about 800 strong at the outset, was posted on the far left of the Union line near Lick Creek, guarding a vital bridge and isolated from the rest of Sherman’s division. When the Confederate surprise attack struck on Sunday morning, April 6, Colonel Mason later claimed his men were unarmed and scrambling to position. Lt. Col. Barton Kyle fell mortally wounded early in the fight (one of 57 men killed from the 71st that day). Amid intense artillery and musket fire, the regiment gave way. Exactly what happened next has been debated for over 150 years – did the 71st Ohio panic and flee the field, or conduct an orderly retreat under impossible odds?

Contemporary accounts were harsh. General Ulysses S. Grant wrote that Colonel Mason “led [his] regiment off the field at almost the first fire,” and that Mason came to him “with tears in his eyes” after the battle, mortified and begging for another chance. Sherman’s report simply noted the 71st was not found with the brigade after a certain point. Fellow soldiers in the adjacent 55th Illinois felt “abandoned” by the 71st’s withdrawal. In Northern newspapers, the regiment (among others from Ohio) was openly accused of cowardice. One Ohio lieutenant, Elihu S. Williams, was so incensed by the “slanderous reports” that he offered to give a “plain, unvarnished tale” to clear the regiment’s name.

The truth is complex. The 71st did sustain serious losses – 57 killed and 51 missing in the chaos – suggesting many soldiers stood and fought longer than the critics acknowledged. Some eyewitnesses later testified that Colonel Mason tried to rally a second line 150 yards to the rear and that the unit became scattered but not wholly craven. But in the end, the 71st did leave the field in disarray on April 6th, earning Colonel Mason the derisive nickname “Runaway Mason” in the army rumor mill. The regiment spent the second day of Shiloh regrouping in the rear.

Despite the blemish on its record, the 71st Ohio remained in service and Mason implored his superiors for a chance at redemption. The men of the 71st, many likely humiliated by the aspersions, were determined to prove themselves. Unfortunately, their next trial would only deepen the controversy.

“The Cowardly Colonel”: Surrender at Clarksville and Aftermath

After Shiloh, the under-suspicion 71st Ohio was pulled from frontline action and assigned garrison duty in Tennessee. In April 1862 they were ordered to occupy Fort Donelson (which had fallen to Union forces in February) and the nearby town of Clarksville, Tennessee. Perhaps higher command thought this quieter post would keep Colonel Mason out of trouble while giving the regiment time to steady itself. The 71st split its companies between garrisons at Fort Donelson and Clarksville through the summer.

On August 18, 1862, disaster struck the 71st’s reputation again. At Clarksville, Col. Mason faced what he believed was a superior Confederate force led by guerrilla raider Col. Adam Rankin “Stovepipe” Johnson (so nicknamed for his use of fake cannon made from stovepipes). Johnson’s rebels – perhaps only 200–300 strong – bluffed the Union garrison. Initially Mason refused a demand to surrender, but soon lost his nerve. Without firing a shot, he capitulated, handing over 125–200 Union soldiers as prisoners. News of this “sad surrender” enraged the Northern press. One Democratic-leaning Ohio newspaper, the Western Standard, blasted Mason as “the cowardly Colonel of the 71st regiment [who] went into the service not from motives of patriotism, but to win a name and fame that would carry him into the Halls of Congress”, sneering that “his record is made”.

President Lincoln’s patience had run out. Just four days later, by order of the President, Col. Rodney Mason was cashiered (dishonorably discharged) for repeated acts of cowardice in the face of the enemy. Virtually all the regiment’s officers who were captured with Mason were also dismissed. An attempt by Ohio politicians to reinstate Mason was firmly rebuffed by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who argued that overturning such a judgment would only demoralize the army. Mason’s military career was effectively over. (He would live until 1893 as a civilian lawyer and patent officer, his name forever tied to disgrace – though as we’ll see, his men later took a kinder view of him.)

What of the enlisted soldiers of the 71st OVI after their colonel’s downfall? Despite the humiliation, the rank-and-file “soldiered on” . The regiment remained on duty in Tennessee under new leadership. Lt. Col. Henry K. McConnell eventually took command (he would be promoted to colonel and lead the regiment through the end of the war). For many months, the 71st performed unglamorous guard and garrison assignments. They protected the vital Louisville & Nashville Railroad supply line, with headquarters at Gallatin, TN, through late 1863. They skirmished occasionally with guerrillas and Confederate cavalry raiders like John Hunt Morgan, but mostly endured the monotony and low-level dangers of occupying hostile territory.

Life in garrison had its own challenges and insights. Gallatin, for instance, was full of “contrabands” – formerly enslaved people who had fled to Union lines for refuge. By 1863, with the Emancipation Proclamation in effect, hundreds of runaway slaves camped around the post. The 71st Ohio’s soldiers witnessed the formation of a U.S. Colored Troops regiment (the 14th USCT) there, and often employed Black men as laborers on fortifications. Captain W. A. Hunter of the 71st noted that these freedmen were doing “the drudgery of war” and quipped they had “just as much right to do the drudgery of war as the white [men]”. Private John M. Piles of Company E went further, writing in a letter, “I say arm every Negro to kill every Rebel.”. Such comments reflected a shifting attitude among Union soldiers, who by that stage of the war increasingly accepted African Americans as allies and soldiers.

Garrison duty also meant coping with disease and boredom. The regiment’s morning reports from 1862–63 record more men lost to illness than enemy bullets. Camps in the Tennessee heat were rife with malaria and dysentery, which hit the 71st hard after Shiloh. One soldier, Pvt. Thomas M. Carey of Company I, is a case in point. The regimental Descriptive Book lists Carey as a 5’9” carpenter with gray eyes and light hair, age 24 at enlistment. Carey was “reported sick” on the first day of Shiloh and was ill through April, May, and June 1862. Many soldiers went home on sick furlough to recover; Carey did so in late 1862, but then overstayed his leave. By early 1863 he was marked absent without leave and eventually deserted in April 1863 when the regiment was at Camp Chase, Ohio. Remarkably, he returned to duty by July 1863 and served out his term, even becoming a color guard by 1864. His mixed record of illness, desertion, and redemption was all carefully recorded in the regimental books. Such details illustrate how the morning reports and ledgers tracked each man “present or accounted for” every day, providing a paper trail of the regiment’s fluctuating health and numbers.

Throughout late 1862 and 1863, the 71st Ohio saw no large battles, which helped them rebuild their strength and discipline. By early 1864, the regiment (or at least those who had reenlisted as veteran volunteers) earned a furlough home. In February 1864, the men returned to Troy, Ohio on leave, where townspeople feted them with speeches and food – a testament to the community’s continued support despite the regiment’s checkered past. Col. McConnell then led five companies of the 71st on an anti-guerrilla expedition in Tennessee in early 1864. He proudly reported home, “Our boys chased the rebels into caves in the mountains and then lit candles and went in after them. We can beat the rebels bushwhacking in their own country.”. This aggressive action helped burnish the 71st’s reputation as it prepared to rejoin major Union offensives.

Back Into the Fray: Atlanta and the Franklin–Nashville Campaign

In mid-1864, after long months of guard duty, the 71st Ohio Infantry finally rejoined a field army for a major campaign. In July, they were reassigned from rear posts to Sherman’s Army in northern Georgia. Arriving in time for the tail end of the Atlanta Campaign, they were placed in the 4th Army Corps (Army of the Cumberland). The 71st participated in the Siege of Atlanta (July–August 1864) and the flanking move to cut off the city’s railroads. In late August they saw action at Lovejoy’s Station and notably at the Battle of Jonesboro (August 31–Sept 1, 1864), where Sherman’s forces forced the Confederates to evacuate Atlanta. During these fights, the regiment deployed as skirmishers out front. Sergeant William T. Hunter wrote proudly from near Jonesboro that “Half of the 71st were on the skirmish line and behaved first rate.” Such praise was a far cry from the sneers of ’62.

With Atlanta fallen, the 71st OVI joined the Union pursuit of Confederate General John Bell Hood during the fall of 1864. Hood attempted to lure Sherman back by moving north into Alabama and Tennessee. Instead, Sherman sent the 4th Corps and others back under General George Thomas to deal with Hood, while he marched to the sea. Thus the 71st Ohio found itself in the Franklin–Nashville Campaign in November–December 1864, the climactic battles of the Western Theater.

At the Battle of Franklin (November 30, 1864), the 71st Ohio was part of 4th Corps’s 3rd Division defending the Union line against Hood’s furious frontal assault. Franklin was a bloody affair (though the 71st’s specific role is less documented in surviving anecdotes). The Union line held, and Hood’s army was badly mauled. Just two weeks later came the decisive Battle of Nashville (December 15–16, 1864), where the rejuvenated 71st Ohio would fully redeem its honor. On the second day at Nashville, the regiment took part in the grand charge that shattered Hood’s remaining forces. Captain William H. McClure (by now commanding a portion of the regiment) recalled how before the assault, troops “piled up their knapsacks” knowing the charge would be so hazardous that even the bravest men turned pale: “big strong men I never knew to flinch would turn white around the mouth [and] swallow their Adam’s apple.” It was a moment of high drama and understandable fear – but the men went forward anyway. The 71st Ohio advanced across tough ground under fire, and in the victorious rush they helped overrun the Confederate works.

The cost at Nashville was significant. The 71st officially suffered many casualties in the battle, including 2 officers and 19 enlisted men killed. Many of those wounded would succumb in hospitals in the following days. Yet the victory was complete. One could say that on the fields of Nashville, the 71st Ohio Volunteer Infantry finally erased the stigma of Shiloh. No one doubted their courage in that crucial battle. As Hood’s beaten army retreated, members of the 71st joined the chase down to the Tennessee River.

Winter quarters in early 1865 found the regiment in northern Alabama and eastern Tennessee. In April, as the war drew to a close, the 71st received word of Lee’s surrender in Virginia, followed shortly by the shocking news of President Lincoln’s assassination. Private John M. Piles wrote to his wife on April 16, 1865, “My heart is very sad over the death of our president in cold blood… How sad every heart is as we have lost one of the noblest men we will ever see.” The war’s end was bittersweet for these veteran Buckeyes – triumphant, yet marred by national tragedy.

In June 1865, the 71st Ohio, along with much of the 4th Corps, was sent on one final odyssey: down the Mississippi to New Orleans, and then over to Texas for occupation duty. Stationed around San Antonio that summer, they guarded the Mexican border (with an eye on French imperial intrigues in Mexico) until finally mustering out on November 30, 1865. Of the roughly 900 men who had enlisted, only 377 were left to be discharged in Texas at war’s end. The regiment had lost 206 men during service – 69 killed or mortally wounded, and 137 dead from disease.

Aftermath and Reunion: Setting the Record Straight

The survivors of the 71st Ohio returned home with a mix of pride and poignancy. They had endured one of the war’s rockiest journeys. In 1866, Ohio’s adjutant general officially acknowledged their service, and over time the sting of early accusations faded. At regimental reunions in the post-war decades, the veterans of the 71st actually took steps to restore Col. Rodney Mason’s good name. At their 35th reunion, Capt. William McClure – now living in Kansas – wrote a letter about Shiloh, stating “no particular officer was to blame that day and Col. Mason was not the coward he was made out to be.” The gathered old soldiers passed a resolution endorsing McClure’s letter, effectively absolving Mason in their eyes. It was a generous act of forgiveness from men who had every reason to hold a grudge. For the 71st Ohio’s veterans, their Civil War service was about more than one man’s failings – it was about comradeship, perseverance, and final victory.

Many notable members went on to live productive lives. Corporal Charles Marley Anderson of Company B became a U.S. Congressman. Captain (later brevet Major) Solomon J. Houck, who had been provost marshal in Gallatin, returned to Ohio and remained a community leader. Major James W. Carlin, one of the regiment’s early officers, survived the horrors of Andersonville prison only to perish tragically in the explosion of the steamboat Sultana in April 1865 while en route home. Lt. John Davis, another Andersonville survivor from the 71st, miraculously lived through the Sultana disaster. And Colonel (brevet Brigadier General) Henry McConnell led the regiment through its redemption and mustered out with the unit, later serving in public roles in Ohio. Each soldier’s story – whether heroic, tragic, or humble – forms part of the rich tapestry of the 71st OVI’s history.

New Light on Old Records: The 71st OVI Regimental Ledgers in the Research Arsenal

One exciting development for researchers and descendants of 71st Ohio soldiers is the recent digitization of the regiment’s official ledgers and record books. These historical documents, now available via the Research Arsenal database, offer an intimate day-to-day look at the regiment and invaluable data on individual soldiers. Surviving 71st OVI records that have been scanned include:

Descriptive Book (Companies A–K)

What it is: A “Descriptive Book” was essentially a roster of all men in the regiment, organized by company, with personal details and service notes. The 71st’s descriptive book lists each soldier from Companies A through K, recording information such as name, age, place of enlistment, physical description (height, complexion, eye and hair color), occupation, and enlistment date. It often also included remarks on each man’s service – for example, promotions, transfers, wounds, desertions, or death. This book is a goldmine for genealogists: it puts a face (figuratively) to the names on the muster roll. A researcher can discover, for instance, that their ancestor was a 5-foot-8 farmer with blue eyes who enlisted at Troy in October 1861.

Why it’s valuable: The descriptive book provides personal descriptors and vital stats not found in basic muster rolls. If you’re tracing family history, these details help confirm identity (distinguishing your John Smith from the next) and paint a picture of the soldier. Moreover, any notations in the remarks column can summarize that soldier’s war – noting if he was killed in action, discharged early, or served full term. In the case of Pvt. Thomas M. Carey (Co. I) mentioned earlier, the descriptive book (and associated service cards) document his entire rollercoaster: from enlistment, to periods of illness around Shiloh, to an AWOL incident and return to ranks, all the way to his mustering out in 1865. Having this book digitized means researchers can search for any name and see that individual’s entry exactly as recorded in the 1860s, which is immensely satisfying for descendants seeking a personal connection to their ancestor.

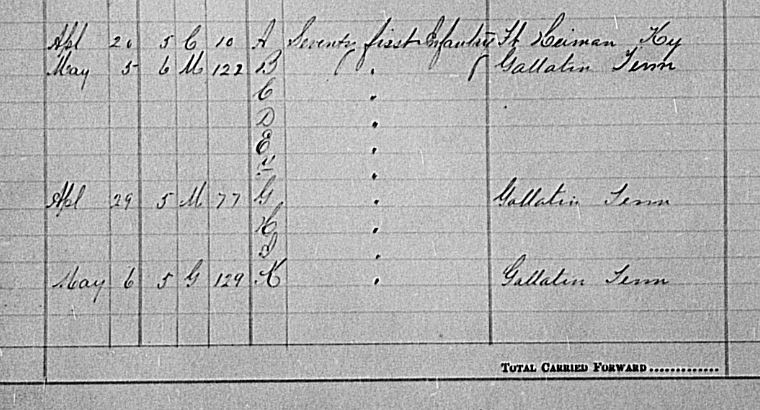

Morning Reports (Companies A–E) & Morning Reports (Companies F–K)

What they are: The morning report was a daily company-level log kept by the first sergeant, reporting the unit’s strength and status each day. Every company in the 71st Ohio maintained its own morning report book. The Research Arsenal has preserved the morning reports for companies A through E in one volume, and F through K in another. Each daily entry typically notes how many officers and men were present for duty, absent, sick, on detached service, on leave, etc., along with any changes since the previous report (such as transfers, returns, deaths, or new admissions to the sick list). These reports were signed each morning by the company 1st Sergeant and an officer, then consolidated up the chain. As one period source described, every man was either “present” or “accounted for” in the morning report – no one was simply forgotten.

Why they’re valuable: Morning reports are perhaps the most revealing day-to-day record of a unit’s condition and routine. For researchers, they offer a granular view of camp life and attrition. Want to know on what date your great-great-grandfather fell ill, or returned from furlough, or was noted “absent – missing after battle”? The morning reports will tell you. For example, a morning report for Company E in April 1862 might list 3 men “sick in hospital” (possibly including Pvt. Carey who reported sick at Shiloh), 2 “absent without leave,” 1 “killed in action April 6,” and so on. By flipping through, you can literally watch the ebb and flow of a company: before a battle, company strength might be 80 present; the day after, 50 present with the rest accounted for as killed, wounded, or missing. You see the toll of battlefield attrition, but also of sickness and recovery – those long periods where more men died from disease than combat. Morning reports also record promotions or attachments (e.g. “Sgt. John Doe detailed as brigade guard”). In short, these ledgers illuminate the daily life of the common soldier, the impact of harsh campaigns (straggling, illness, casualties), and even administrative rhythms like furloughs and returns. Historians can use them to analyze how effective strength fluctuated over time, while family researchers might use them to pinpoint a relative’s whereabouts on a given date. With the Research Arsenal’s digitization, one can search these morning report books by name or date, rather than paging through fragile originals – a huge boon.

Order Book (Companies A–G)

What it is: Military units kept order books to record official orders received and issued. The surviving Order Book for the 71st Ohio covers Companies A–G (why H–K are absent is unclear – possibly a separate volume was lost). In this ledger, one would find copies of regimental and company orders, such as duty assignments, guard details, court-martial proceedings, promotions, or directives from higher headquarters that were to be circulated to the companies. For example, if the brigade issued an order to send 20 men on a foraging party, or if the regimental commander published a list of men to be transferred to the Veteran Reserve Corps, those would be copied into the order book. It effectively served as the official memo book for the regiment and its sub-units.

Why it’s valuable: The order book gives context to the regiment’s operations and administration beyond the battlefield. It can reveal tidbits like: Who was the acting commander of Company C when Lt. So-and-so was on leave? What instructions were given to the regiment on the eve of a certain march or battle? Were any soldiers of the 71st commended or disciplined in orders? For descendants, finding a mention of an ancestor in an order (perhaps detailing them as a teamster, or noting their promotion to corporal) is exciting evidence of their role. Even when individual names aren’t involved, the orders shed light on the daily duties and organizational life of the regiment – something often glossed over in battle narratives. The fact that we have this book for companies A–G means researchers can study how the 71st was managed internally. For instance, an entry from August 1863 might instruct Company B to furnish 10 men for picket duty at Gallatin, or record General Orders from army headquarters about maintaining sanitary camp conditions. These details enrich our understanding of the 71st OVI’s experience. Now, thanks to digitization, one can read these orders in the original 19th-century handwriting, which adds an authentic touch to any research project.

Regimental Descriptive & Consolidated Morning Report Book

What it is: In addition to company-level records, Civil War regiments often kept regimental-level books. This particular volume appears to serve a dual purpose: a Regimental Descriptive Book and a Consolidated Morning Report Book combined. The regimental descriptive section likely summarizes key information on the regiment’s officers and perhaps an overview roster of enlisted men (essentially a higher-level abstract of the company descriptive books). The consolidated morning reports are the daily or periodic summaries compiled from all the companies’ morning reports. Each day, the adjutant of the 71st would take the ten company reports and merge the numbers to report “Regiment present for duty: X officers, Y men; absent: Z; on extra duty: …” and so forth. These consolidated reports were sent up to brigade and army headquarters. The regimental morning report book would contain a copy of each of those daily summary reports, often with additional notes.

Why it’s valuable: While the company morning reports show granular detail, the consolidated regimental morning reports show the big picture of the regiment’s status at a glance. Researchers can follow the arc of the 71st OVI’s strength over time – for instance, seeing it with nearly 900 men in early 1862, down to perhaps 500 effectives after the ravages of disease and detachments in 1863, and back up a bit with new recruits in 1864, then dropping again after heavy losses at Nashville. These figures are crucial for understanding how much combat power the unit really had at various points. Moreover, any extraordinary events sometimes are noted in regimental reports. The adjutant might annotate a day’s report with “Battle of Jonesboro – Co. C lost 2 killed, 5 wounded” or “Skirmish at Pickett’s Hill – 3 men missing” as an explanation for changes. Such notes provide a concise chronicle of the regiment’s engagements and attrition. For descendants, if your ancestor’s company reports are missing, the regimental report still confirms if he was present with the regiment. And the descriptive portion of this book can be a fallback source for soldier data, or unique information on officers (e.g. a list of field and staff officers with personal details and service record). In essence, this book ties all the companies together and is key for regimental-level research. Having it digitized means one can easily track the regiment’s overall condition day by day – a task that previously required visiting an archive and laboriously copying data by hand.

Regimental Letter, Endorsement & Order Book

What it is: The final ledger now in the Research Arsenal’s 71st Ohio collection is a Regimental Letter Book, which also includes endorsements and orders. During the Civil War, regimental headquarters corresponded frequently with higher commands and sometimes with other units or officials. They kept “letter books” copying all outgoing correspondence (and sometimes important incoming letters) for record-keeping. An endorsement is a form of official notation added when forwarding a letter up or down the chain (“Respectfully forwarded by Col. ___ with the following remarks…”). This volume likely compiles all the formal letters sent by the 71st Ohio’s commanders – whether requests for supplies, reports of activities, lists of casualties after battles, or disciplinary matters – as well as any headquarters orders specific to the regiment. For example, after Shiloh, the acting commander might have written a report to brigade HQ explaining the regiment’s losses; or later, Col. McConnell might have sent a letter recommending a lieutenant for promotion. Such communications would be copied into the letter book.

Why it’s valuable: The regimental letter and order book is perhaps the most narrative and personalized record among these ledgers. Here, the dry numbers of morning reports give way to actual written dispatches in the words of the officers. This is where you might find a poignant letter detailing the aftermath of a battle (“I regret to report the death of Lt. Kyle, who fell while bravely encouraging his men…”), or a request (“Many of our men are barefoot and require new shoes”), or even the proceedings of a regimental court-martial for a soldier (which could name names and describe offenses). For historians, such documents are primary evidence of the regiment’s experiences and the concerns of its leaders. For family researchers, there is a chance (though not a guarantee) that an ancestor is mentioned in correspondence – perhaps in a list of honorees, or as a misbehaving private in a disciplinary report, or as one of “five men of Company D” praised for some act. Even if individual soldiers aren’t named, these letters provide color and context: they show what challenges the regiment faced (illness, logistics, combat reports) in the very voices of those in command. Reading them can be as engaging as reading someone’s mail – you get authentic content like an endorsement from brigade command noting “the gallant conduct of the 71st OVI in the late engagement at Nashville” or a War Department order relieving the regiment from duty in Texas. Now that this letter book is digitized, anyone can dive into these communications and perhaps discover new anecdotes. It’s like opening a time capsule of the regiment’s administrative life.

Using the Research Arsenal for the 71st Ohio’s Records

All the above records – the descriptive book, morning reports, order books, and letter book – have been carefully scanned and made available in the Research Arsenal’s online Civil War database. For researchers, this means the 71st Ohio’s paper trail is accessible with a few clicks. You can search for a soldier’s name and potentially find every ledger page where he’s mentioned, or browse by date to see what was happening on a particular day of the war. The scans show the original handwriting, which adds authenticity (and occasional challenge in deciphering old script!). The Research Arsenal has also helpfully indexed many names, making it easier to find ancestors in these documents.

For example, if you’re looking up Sgt. Daniel W. Ellis (Co. C) – a soldier from Piqua whose preserved letters to his sweetheart Mary give us additional insight into the 71st’s daily life – you might search his name and discover entries in the morning reports noting when he was on duty or absent, corroborating the timelines in his letters. Or if you’re curious about officers, you might find Capt. Elihu S. Williams (Co. K) mentioned in an endorsement or order regarding his resignation or duties (Williams, the New Carlisle attorney, resigned in 1863 and later received local praise despite partisan sniping). Each discovery helps connect the dots between the official record and personal stories.

Perhaps most importantly, these records allow us to appreciate the humanity behind the history. The morning reports quantifying daily sickness, the descriptive rolls measuring each man, the orders detailing rations or marches – all remind us that an army is not just its generals and battles, but its regular people managing day-to-day life. The 71st Ohio Volunteer Infantry’s journey – from raw recruits “sober to a man” after a Piqua farewell dinner, to the hell of Shiloh, the ignominy of Clarksville, the long vigil in Tennessee, and the final storming of Nashville – can now be studied not only in secondary histories but through the very pages those soldiers wrote and signed.

Conclusion: A Regiment Reborn Through Research

The 71st Ohio’s Civil War odyssey is a tale of resilience and redemption. Initially maligned for failure under poor leadership, these Ohioans proved their mettle in the end – chasing guerrillas in dark caves, holding the line at Franklin, and braving the fire at Nashville. Along the way they interacted with freed slaves, endured illnesses that decimated their ranks, and witnessed pivotal moments of the war’s end. Their story, once “particularly varied” and sometimes romanticized in local histories, can now be explored in vivid detail thanks to primary sources.

For descendants and history buffs, the newly available regimental ledgers in the Research Arsenal are a treasure. Whether you want to confirm a cherished family legend (“Grandpa was wounded at Nashville”) or simply understand daily life in a Civil War regiment (“How many men answered roll call on a cold December morning?”), these records deliver. They underscore the significance of tools like morning reports – often overlooked – which show us the health, morale, and attrition of a unit beyond what battlefield reports convey. A morning report can reveal a silent killer like dysentery sweeping through the camp, or note the return of a long-absent soldier just in time for a campaign. The 71st Ohio Volunteer Infantry’s documents particularly highlight how a unit can recover from setbacks: by late 1864 their reports and letters tell of a veteran regiment full of confidence and competence, a far cry from the faltering outfit of Shiloh.

In researching your favorite regiment or ancestor, remember that history lives in these details. The 71st Ohio Volunteer Infantry’s saga – equal parts infamy, endurance, and triumph – is now more accessible than ever. As you flip through a scanned ledger page or read a captain’s letter in flowing penmanship, you form a tangible connection with those Union soldiers of long ago. And perhaps, in those pages, you’ll hear echoes of the musket volleys at Shiloh, the reveille bugle at Gallatin, or the cheers of victory at Nashville. This is the lasting legacy of the 71st OVI, brought to life through the marriage of historical archives and modern research tools.

Sources:

- Research Arsenal: 71st OH Regimental Ledgers (RG94.6851106)(71st Ohio Volunteer Infantry)

-

National Park Service, “71st Regiment, Ohio Infantry” (unit history and service timeline)nps.govnps.gov (71st Ohio Volunteer Infantry)

-

Tom Stafford, Springfield News-Sun, “71st Ohio Volunteer Infantry had checkered reputation in Civil War” (2011) – includes excerpts from Martin Stewart’s history Redemption: The 71st OVIspringfieldnewssun.comspringfieldnewssun.comspringfieldnewssun.comspringfieldnewssun.comspringfieldnewssun.comspringfieldnewssun.comspringfieldnewssun.com

-

Derrick Lindow, “The Curious Case of the 71st Ohio” (Kentucky Civil War blog, 2018)kentuckycivilwarauthor.comkentuckycivilwarauthor.comkentuckycivilwarauthor.com

-

Troy Historical Society, Civil War Soldiers from Piqua at Shiloh (biographical details on 71st OVI soldiers)thetroyhistoricalsociety.orgthetroyhistoricalsociety.org

-

Claire Prechtel-Kluskens, NGS Magazine 2012, “Compiled Military Service Records” (overview of regimental descriptive book contents)twelvekey.com