From Monmouth to the Cumberland: The 83rd Illinois Infantry

From Monmouth to the Cumberland: The 83rd Illinois Infantry

Formation and Early Service in Illinois

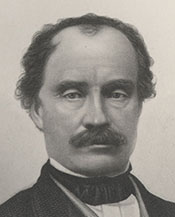

In the summer of 1862—amid a new call for volunteers following heavy losses in the spring campaigns—patriotic fervor in western Illinois gave rise to the 83rd Illinois Volunteer Infantry. The regiment was organized at Monmouth, Illinois, drawing its ten companies from Warren, Mercer, and Knox counties. On August 21, 1862, 936 officers and men mustered into Union service under the command of Colonel Abner C. Harding, a 55-year-old local businessman who had remarkably enlisted as a private and been elected colonel by his men. Camped on the fairgrounds outside Monmouth, these fresh recruits began the transition to soldier life. Early regimental orders issued at Camp Warren (as the encampment was known) reveal the strict discipline imposed from the outset. General Order No. 1, dated August 24, 1862, forbade any member of the 83rd Illinois Infantry from leaving the limits of camp “without a leave of absence from regimental headquarters”. This meant no soldier could slip away to town or home without written permission – a necessary rule to keep this new unit together and focused. Two days later, General Order No. 2 established the regiment’s daily routine, regulating roll calls, drill schedules, and other duties to instill military order in the volunteers. By late August the men of the 83rd were deemed ready to move out, having transformed from a collection of farm boys and townsmen into an organized fighting unit. They left Monmouth on August 25, traveling by rail and steamboat via Burlington, Iowa, and St. Louis toward Cairo, Illinois. Reaching Cairo on August 29, the regiment reported to Brigadier General James M. Tuttle, who commanded that important Union river port at the southern tip of Illinois. Within days, orders came for the 83rd Illinois to head south into the war’s Western Theater, where it would spend the next three years guarding strategic strongholds and supply lines.

Garrison Duty for the 83rd Illinois Infantry at Fort Donelson and the Battle of Dover

In early September 1862, the regiment steamed up the Tennessee River to Fort Henry (recently captured by Union forces), then marched on to Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. Fort Donelson, Tennessee had fallen to Ulysses S. Grant in February 1862, a major Union victory. Now the 83rd Illinois Infantry was tasked with holding this vital post and the surrounding region. They would remain garrisoned at Fort Donelson for the next year, a period marked by ceaseless guard duty and skirmishes. The countryside around the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers was “infested with guerrillas,” as one account recorded, and the 83rd found itself in near-daily contact with irregular Confederate cavalry and bushwhackers. These running fights, though often small in scale, were dangerous. In one sharp skirmish at Waverly, Tennessee and another at Garrettsburg, Kentucky, the regiment saw particularly intense action. Such encounters honed the unit’s mettle and kept them alert.

The greatest test for the 83rd Illinois Infantry came on February 3, 1863, in what became known as the Battle of Dover. On that day, a Confederate force of about 8,000 veteran cavalry and infantry under Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler and Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest launched a ferocious attack to retake Fort Donelson and the town of Dover. The garrison at Donelson was vastly outnumbered – it consisted mainly of nine companies of the 83rd Illinois (about 600 men present) and a single Illinois light artillery battery. Colonel Harding, commanding at Fort Donelson, refused to surrender. His men dug in and, with the help of the fort’s artillery, “successfully resisted the attack” by the Confederate raiders over the course of a seven-hour battle. The 83rd Illinois Infantry fought from 1:30 in the afternoon until 8:30 PM in cold winter rain, holding the fort against repeated assaults and even a demand for surrender. By nightfall, Wheeler and Forrest withdrew, having failed to break the Union defenses. The victory at Dover was a proud moment for the raw Illinois regiment. However, it came at a steep price. The 83rd Illinois suffered 13 men killed and 51 wounded in the fight. Among the fallen were Captain P. E. Reed of Company A, First Sergeant James Campbell of Company C, and the regiment’s quartermaster, Lieutenant Harmon D. Bissell. One of the wounded was Captain John McClanahan of Company B, who was shot while repositioning his men and later died of his injuries.

The morning reports (scanned and made available here by the Research Arsenal) for February 4th in the regiment’s ledger would have reflected these losses – noting the sudden drop in “present for duty” and listing the men killed or incapacitated the previous day. Such primary records humanize the toll of battle beyond the statistics, naming each casualty and often recording their fate. For their heroism at Fort Donelson, the soldiers of the 83rd earned high praise. Colonel Harding’s “gallant conduct” in the defense won him promotion to brigadier general, and the regiment gained a reputation for steadfast courage. A Confederate newspaper, amazed at the stand made by what they assumed was a much larger force, dubbed Harding’s command “those d—d stub–born Yankees at Donelson.” The Battle of Dover cemented the 83rd Illinois as battle-tested veterans.

Holding the Line: Skirmishes and Guerrilla Warfare

After the repulse of Forrest and Wheeler, the 83rd Illinois Infantry continued to perform critical garrison and patrol duties in the Fort Donelson area throughout 1863. Confederate guerrillas and scouting parties remained active in northern Tennessee and Kentucky, requiring constant vigilance. The regiment’s companies were sometimes dispersed to cover more ground: in mid-1863, five companies of the 83rd (the right wing) were sent to Clarksville, Tennessee, a town upriver towards Nashville, while the rest stayed at Fort Donelson. From these outposts the Illinoisans engaged in expeditions to disrupt enemy guerrillas and cavalry raids. They joined operations under Maj. Gen. Lovell H. Rousseau and others, chasing elements of Forrest’s and Wheeler’s commands who threatened Union supply lines. The soldiers often found themselves marching through swamps and forests, tearing up Confederate camps or ambushing raiders – the dirty, grinding work of counterinsurgency that seldom made headlines. Small-scale fights were frequent. For example, on August 20, 1864, Captain William M. Turnbull of Company B led 11 men out from Fort Donelson in pursuit of a band of five guerrillas who had been stealing horses. They rode into an ambush. A larger group of pro-Confederate partisans lay in wait in the woods. Turnbull and seven of his troopers were killed in a sudden volley; one soldier had both legs broken and was left for dead in a barn, where he was “cowardly murdered” by guerrillas who discovered him helpless. Only three of Turnbull’s patrol survived to tell the tragic tale. This harrowing incident, recorded in both the regimental order book and later histories, underscores the constant peril faced by the 83rd Illinois even when no major battles were underway. Through 1864, the regiment was responsible for guarding over 200 miles of supply lines and communications, including roads, telegraph lines, and river routes vital to the Union armies operating in the Deep South. The men built blockhouses, manned signal posts, escorted wagon trains, and patrolled roads to prevent sabotage. According to one account, “during the year 1864, the regiment had some two hundred miles of communications to guard and much heavy patrol duty”, duties which often stretched the companies thin across isolated outposts. Their morning report ledgers from this period show constant detachments of squads on scouting duty or stationed at remote posts, as well as the return of veterans on furlough and arrival of new draftee replacements that helped fill the ranks. By late 1864, as General Sherman marched to the sea and Confederate General Hood moved north into Tennessee, the 83rd Illinois was pulled into more concentrated duty. The regiment was ordered to Nashville, Tennessee, where it served as provost guard during the winter of 1864–65. In this role, the Illinois soldiers maintained order in the crowded Union-held city, escorted prisoners and supplies, and likely took pride in seeing the Confederate Army of Tennessee decisively defeated outside Nashville in December 1864.

Throughout these long months of garrison service, the 83rd Illinois had few opportunities for glory, but its contributions were invaluable to the Union war effort. They denied the enemy a foothold in Tennessee, protected civilians from lawless guerrillas, and ensured that Union armies operating further south (like Sherman’s) stayed reliably supplied. The regiment’s Descriptive Book and Casualty Book further testify to the hardships endured: beyond combat deaths, disease took a steady toll in the unhealthy camp environments. In total, the 83rd Illinois Infantry lost 1 officer and 82 enlisted men to sickness (often dysentery, typhoid, or exposure), in addition to 4 officers and 34 enlisted men killed or mortally wounded in action. These ledger entries of hospitalizations and burials, written in faded ink, give somber evidence of the less-glamorous battle the regiment fought against illness. Each name and date in the books represents a grieving family back home and a sacrifice for the Union cause.

Muster-Out and Legacy of the 83rd Illinois Infantry

With the Confederacy collapsing in the spring of 1865, the veteran regiments raised in 1862 were finally allowed to go home. On May 31, 1865, Major General Rousseau issued a special order praising the 83rd Illinois as they prepared to be discharged. He lauded their “soldierly bearing and gentlemanly conduct” and noted he had “not been troubled with complaints against them for disorderly conduct or marauding”, high praise for troops who spent so long on occupation duty. Rousseau declared that “I do not know a regiment in the service whose brave and soldierly bearing more fully entitles it to the respect and gratitude of the country than the Eighty-third Illinois”, a testament to their discipline and reputation. Under the command of Brevet Brigadier General Arthur A. Smith (who had risen from lieutenant colonel), the regiment mustered out in Nashville on June 26, 1865. They returned to Illinois by rail, arriving in Chicago for final pay and discharge on July 4, 1865. After nearly three years away, the weary survivors of the 83rd Illinois marched down Chicago’s streets and then went their separate ways into civilian life. Many would bear the scars of their service—some visible, some hidden—for the rest of their days.

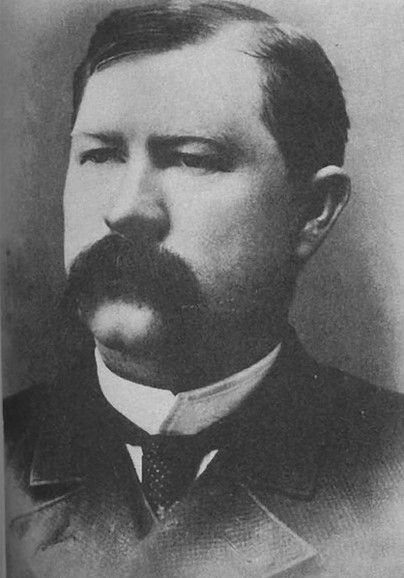

One private in Company C, Virgil W. Earp, would become far better known for his later exploits in the Wild West. Yes, that Virgil Earp of O.K. Corral fame began his fighting days as an 18-year-old in the 83rd Illinois. Enlisting in July 1862, Earp served through the entire war, mustering out with his regiment in 1865. The regiment’s descriptive rolls capture a snapshot of the future lawman at enlistment: Virgil was recorded as “five foot ten with light hair, blue eyes, [a] light complexion, single, [and a] farmer”. Such details, preserved in 160-year-old ledgers, allow us to picture the youthful soldier who would later uphold the law in Dodge City and Tombstone. Click HERE to see Virgil Earp’s enlistment descriptive roll in the Research Arsenal.

Dozens of other men of the 83rd Illinois are similarly described in those pages, from color of eyes to birthplace and occupation, offering a treasure trove for genealogists tracing Civil War ancestors. The Regimental Descriptive Book even noted each soldier’s fate – who re-enlisted as a veteran volunteer, who transferred to the 61st Illinois in June 1865 (a handful did rather than go home), and who perished along the way.

When the regiment disbanded, its story could easily have faded into obscurity, overshadowed by larger battles and more famous units. Yet the veterans kept its memory alive through reunions and the regimental flag they carried with pride. Today, historians and descendants can reconstruct the rich history of the 83rd Illinois largely thanks to meticulously kept ledger books that have survived and been digitized.

Uncovering History Through the 83rd Illinois Infantry’s Ledgers

The Research Arsenal has made available a collection of original 83rd Illinois Infantry regimental ledgers, whose pages offer unparalleled insight into the daily experiences of the unit. These include:

-

Morning Report Ledgers (Companies A–E and F–K) – Daily muster reports noting how many men were present, absent, sick, or on detached service. Researchers can follow the regiment’s strength rising and falling over time. For instance, one can see the sudden drop in effective numbers right after the February 1863 battle, or trace when veterans went home on furlough. These reports also occasionally include remarks on significant events (e.g. “2 men killed on picket – last night” might appear after a skirmish).

-

Descriptive Books (Companies A–K & Regimental) – Detailed registers of every officer and enlisted man who served in the 83rd Illinois Infantry. They record each soldier’s name, age, physical description, occupation, enlistment date, and hometown, as well as notes on their service (promotions, wounds, discharge or death). Through the descriptive books we learn personal details – for example, the entry for Quartermaster Lt. Harmon Bissell would note his tragic death in action on Feb. 3, 1863. These volumes put a human face on the regiment, allowing descendants to identify ancestors and historians to analyze the composition of the unit (average age, occupations, etc.).

-

Order Books and Miscellaneous Records – The Regimental Order Book and Order/Casualty & Miscellaneous Book contain copies of official orders, correspondence, and casualty lists kept by the regimental adjutant. In these pages are found the general orders issued by the regiment (such as the ones from August 1862 quoted earlier) as well as special orders detailing promotions, assignments, or punishments. For example, General Order No. 4, issued at Cairo on August 31, 1862, laid down guidelines for conduct and readiness, stating in part that “the Colonel commanding expects every officer and soldier of the Regiment to faithfully perform his duties” and that company commanders would be held responsible for enforcing all orders. The same books also include casualty reports after engagements, which enumerate the killed, wounded, and missing by name. Reading those lists alongside battle reports in the Official Records can confirm details and sometimes correct them. Moreover, letters and miscellaneous memoranda tucked in these ledgers shed light on day-to-day problems (such as supply issues or disciplinary cases) that rarely make it into history books.

Together, these six ledgers form a comprehensive paper trail of the 83rd Illinois Infantry’s Civil War service. By studying them, one can track the regiment’s journey from its first days in Monmouth – when order book entries like General Order No. 1 emphasized basics like not leaving camp without leave – to its final mustering out, when a farewell order in June 1865 praised the men’s honesty and bravery. The ledgers allow us to hear the voices of the regiment’s officers as they struggled to maintain order and morale, to see the names of every volunteer who filled the ranks, and to understand the administrative side of army life that unfolded behind the front lines.

For history enthusiasts and descendants, access to these digitized records is akin to time-travel. A family researcher might discover an ancestor’s enlistment entry, learning his height and eye color and exactly when and where he served. A Civil War scholar can correlate the morning reports with battlefield accounts, gaining a clearer picture of how an engagement impacted the unit day-by-day. Through the dry official language of these books emerge countless poignant stories – the farmer’s son who died of fever in a hospital tent, the teenaged recruit who survived Gettysburg only to be ambushed by guerrillas, the experienced sergeant promoted after Turnbull’s death to take charge of what remained of Company B.

The history of the 83rd Illinois Infantry is more than a list of dates and battles; it is the sum of the experiences of the nearly one thousand men who served in its ranks. Thanks to the preservation of primary sources like the 83rd’s morning reports, descriptive rolls, and order books, we can piece together those experiences in vivid detail. From the regiment’s humble beginnings guarding a cornfield camp in Illinois, to the thunderous afternoon when they stood firm at Fort Donelson, to the lonely picket posts along the Cumberland River, the story survives in the ink and paper of those ledgers. As Major General Rousseau affirmed in 1865, the 83rd Illinois Infantry earned the “respect and gratitude of the country” through its service. Today, with the help of these digitized records, we can finally give this hard-fighting regiment the recognition and understanding it deserves, and ensure that the lived experiences of the 83rd Illinois Infantry continue to enlighten and inspire future generations.

Sources: The above narrative is drawn from a variety of primary and secondary sources, including the Illinois Adjutant General’s Report and regimental history,(illinoisgenweb.org), official records and correspondence, and the 83rd Illinois’s own surviving ledger books (morning reports, descriptive rolls, and order books) available via the Research Arsenal.