Research Arsenal Spotlight 7: David King Perkins of the USS Seminole

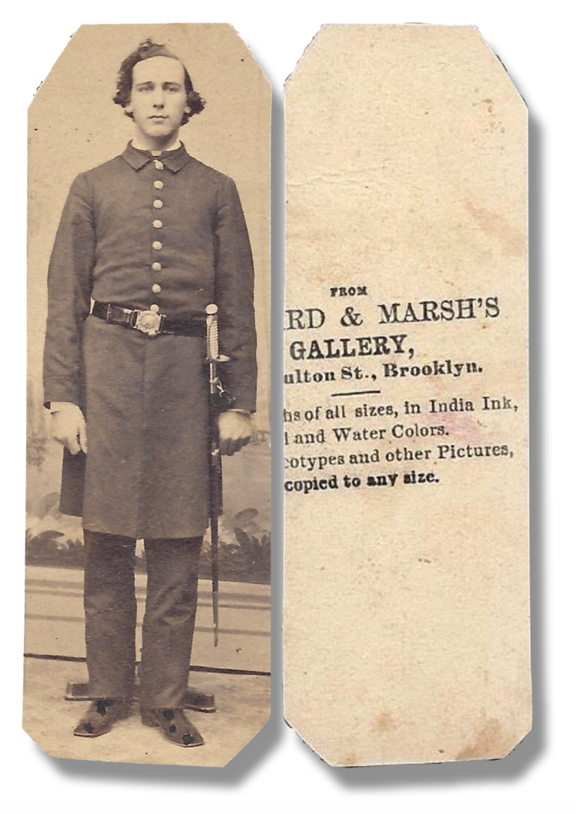

David King Perkins was born in 1843 to Clement T. Perkins and Lucinda (Fairfield) Perkins of Kennebunkport, Maine. On January 30, 1863, he enlisted in the US Navy as a Master’s Mate onboard the USS Seminole. In this collection of eight letters at the Research Arsenal, he writes to his sister, Caroline Amelia Perkins, about his experiences at sea.

David King Perkins and the U.S.S. Seminole

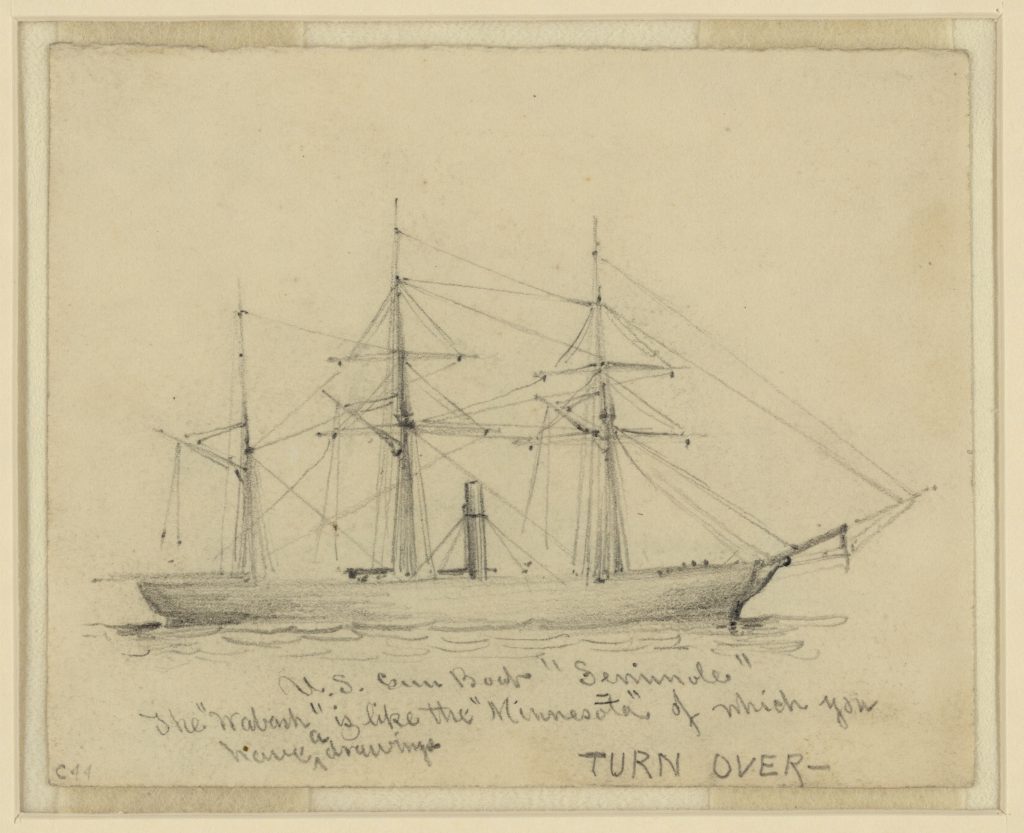

The USS Seminole was commissioned on April 30, 1861 with Edward R. Thomson as commander. The Seminole was a steam sloop-of-war and while David King Perkins was serving was mainly stationed as part of the Western Gulf Blockading Squadron.

David King Perkins’ first letter in the Research Arsenal collection is dated November 26, 1863, about 11 months after he first started serving on the ship. In it he described the boredom that the blockade duty had brought to the crew:

“Everything is about the same here in the Blockade. We have no hopes of getting relieved. I expect we shall have to lay here all winter or until the place is taken. I hope that will be soon for I am most tired of laying here. Since our two new officers came, we have it very easy. Stand four hours watch and then have twenty hours off so I am sure I cannot grumble about having hard times. I improve my spare time by study. We have a very nice old man for an Acting Master. He takes great interest in teaching us young Masters Mates navigation. I shall be an experienced navigator by the time I leave the Navy.”

By April 15, 1864, the USS Seminole was off the coast of Mobile Bay, Alabama, and David King’s Perkins’ spirits seem to have raised somewhat:

“We lay in sight of “Fort Morgan.” When we are in our night stations, we are about three miles from land and five from “Fort Morgan.” There is quite a fleet of vessels here. I think there is twelve in all but twelve does not seem to be enough to stop blockade runners for since we arrived there has been two run the blockade and one a large steamer named the “Auslin.” I feel in hopes we shall be lucky to catch one soon. We have been quite fortunate so far in catching prizes.”

David King Perkins’ Hopes of Promotion

While serving as a Master’s Mate on the USS Seminole, David King Perkins dreamed of advancing his station. In a letter written March 9, 1864, he wrote to his sister that he had taken the examination to be promoted to ensign and was anxiously awaiting the results:

“I have been very busy about my application. I have sent it in to the Commodore but have not heard anything from it yet. However, I hope to soon for I want to know the worst of it. If I pass my examination, it is well and good. If not, I shall not care to stop in the Navy. I cannot make a cent to serve in the capacity as Master’s Mate. If I do not get my promotion as Ensign, I think the Merchant services would be better for me.”

A week later, David King Perkins wrote in a new letter that he still hadn’t received any word on his application:

“When we first arrived here, I applied to the Admiral for permission to be examined for the position of Ensign. I have not heard anything from my application yet and am afraid I shall not. I shall wait a little longer. Then if I do not hear from it, I will forward my recommendation. I think it would be much better if I pass my examination, then I shall not be under obligations to anyone. However, if I do not hear from the Admiral soon, I will forward the recommendation to Father and let him give it to Mr. Moody.”

By the end of the war, David King Perkins served as the Acting Ensign on the USS Seminole.

The USS Seminole Off the Coast of Texas

The USS Seminole participated in the Battle of Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864, though David King Perkins had nothing to say about it to his sister. After undergoing repairs at Pensacola, Florida, the USS Seminole was then sent to Galveston, Texas in September of 1864 and remained along the Texas coast until the end of the war.

On November 3, 1864, David King Perkins’ wrote to his sister about events along the coast:

“Since I wrote to father and Tenie we have had quite an exciting chase. On the night of the 30th, signals were made that a steamer was running out. We immediately slipped our chain and stood off to sea in the direction we supposed the steamer would take. In the meantime, the weather had come in very thick. Quite early in the morning I discovered a suspicious looking steamer. I having charge of the deck at the time, we changed course at once and stood for the stranger. He also changed his course and stood away from us with the hopes of making his escape. We made all sail in chases fired a gun at him, which he did not seem inclined to notice. We were gaining very fast and had him most under our guns when the weather came in very thick and we lost sight of the steamer.

The weather did not clear up until about 2 o’clock. The chase commenced at about 6 o’clock in the morning and we losing sight of the steamer at about 9 a. m. When it had got well cleared up, we again saw the steamer from the masthead but she was a long way off, having steered a different course from us while it held thick. We continued to chase until night came on when we were compelled to give it up, being most out of coal. Had we captured the steamer, it would have probably put three or four thousand dollars in my pocket. But I am afraid there is no such good luck in store for me.

The same night the steamer run out, there are six schooners also run, all of which were loaded with cotton. I believe only one was captured.”

In another letter written about three weeks later, David King Perkins revealed the meagre share of prize money he had accumulated so far:

“It is hardly worthwhile for me to caution you to be prudent and saving. I do not lay up but little money although I am saving, yet my expenses are great. If I was on board a small vessel, I could save much more than I do. This ship has not been very lucky in capturing prizes. My share of the “blockade runner Charleston” amounts to $46.31 which is only a very small sum. Should the steamer “Sir William Peel” be condemned, I shall probably get something quite handsome.”

David King Perkins continued serving on the USS Seminole past the end of the war until November, 1865. He died in California in 1893.

We’d like to extend a special thanks to William Griffing of Spared & Shared for transcribing and sharing these letters.

To read the full collection of David King Perkins letters and thousands of others, sign up for a membership at the Research Arsenal.

Check out some of our other spotlight collections like James A. Durrett of the 18th Alabama Infantry or Albert Henry Bancroft of the 85th New York Infantry.