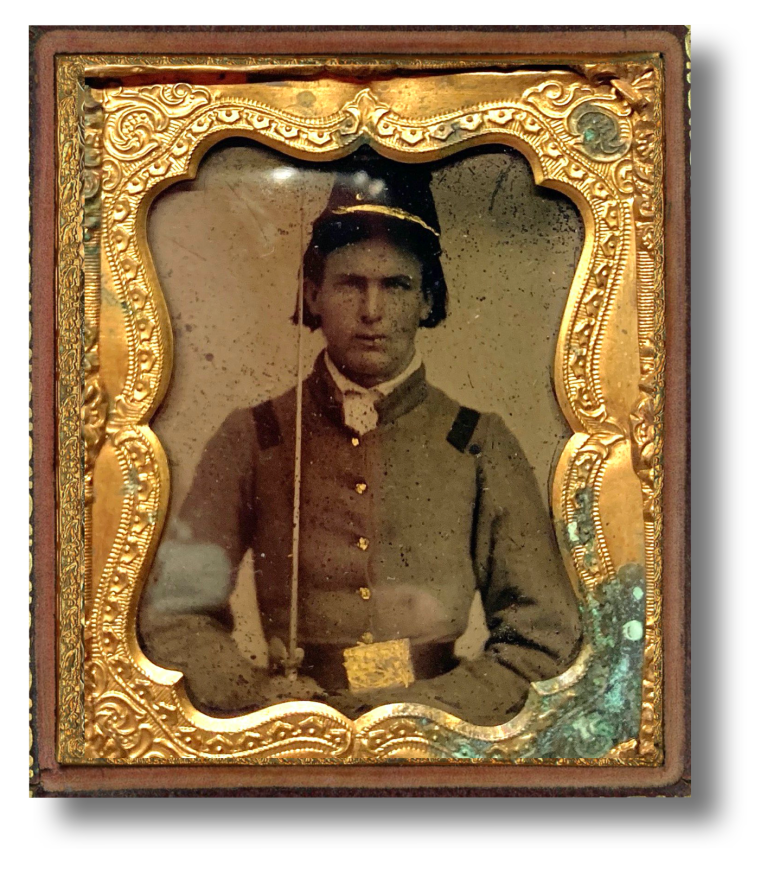

Research Arsenal Spotlight 33: William Clemmons 7th Tennessee Infantry

William Clemmons was born in 1843 to Edwin and Patience (Harris) Clemmons of Lebanon, Tennessee. He enlisted on May 20, 1861 in “The Blues,” company K of the 7th Tennessee Infantry. The 7th Tennessee Infantry was part of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia.

The nine letters in our Research Arsenal collection were all written to Sarah Jane Bettes, William Clemmons’ sweetheart back home. She was the daughter of Ausburn Bettes and Martha Ann (Wilkerson) Bettes.

William Clemmons at Richland Station, Tennessee

William Clemmons’ earliest letters in our collection were written from Richland Station, Tennessee shortly after the regiment was formed. In his first letter to Sarah Jane Bettes, William Clemmons described the size of the camp and his hope that Sarah Jane would send him a photograph of herself.

“Sarah Jane, I wish I could see you now. I could tell you a great deal. There are about five thousand soldiers here. It is not known how long we will stay here—some time perhaps. If we don’t move soon, I think I will get a furlough and come over home in about ten days. I do not know whether I can or not though. If I do come home, I must have your picture. You must have it taken. I promised to give you my picture but the galleries were crowded so that morning, I could not get it taken. I will try and get it taken if I go over home and exchange with you.”

On June 15, 1861, William Clemmons wrote again to Sarah Jane about some recent excitement in the camp.

“This week we have had some excitement in the camp. It was the news day before yesterday that we must be ready at an hours warning to leave here. So we were calculating that we would have to go some distance, not knowing where. But in the evening, a special message came from Nashville changing the order of the moving, so we had more quiet for a while. But about eleven o’clock at night, a gun was fired by a sentinel which created a powerful alarm. The whole camp was in an uproar. I never saw such a time for an hour. Some hollering for guns, some going one way and some another—no one knowing what was the matter. It all turned out to be nothing at last.”

The 7th Tennessee Infantry Fights the Yankees

On August 4, 1861, the 7th Tennessee Infantry was at Huntersville, Virginia, and anticipated a fight with the Union Army at any moment. William Clemmons wrote to Sarah Jane about the large number of troops in the area and his belief that the Tennessee soldiers were much better than those from other states.

“I am enjoying the best of health and in good spirits. We are now close to our enemies. They are thick as pigeons in about 20 miles of here. In two more days, we will be among them. It is supposed that there is about 30,000 Yankees there. There won’t be many there by the time we get among them and jolt them a time or two. They have whipped the Virginians a time or two, but we are the boys they can’t whip so easy. Virginians can’t fight like Tennesseans, Mississippians, Alabamians &c. We are going to whip them out up there and go to Alexandria and drive them out of there and from there on to Washington City and whip them there, and then we will go home. You may look for me this fall for by that time all things will be settled.”

In another letter written on August 20, William Clemmons told Sarah Jane of his eagerness to finally face the Union army in battle.

“We have just received orders to leave here at a moment’s calling. We are going from here to Huttonville and there I expect we have a brush with the Yankees for I am told there is a good number of them there, or round about there. I am “sitting back” ready for one or two of their scalps. I will try real hard to snatch some of them from time into eternity before they get me.”

William Clemmons also wrote of some of the hardships he’d already faced as soldier and the difficulties of life in the field.

“A soldier’s life is a hard life. I have read of wars and the hardships pertaining to them but now I experience the reality, none but a soldier can tell how hard a life it is. Just imagine you see us climbing mountains, wading rivers and creeks, sometimes traveling under a broiling sun, sometimes facing the hardest thunderstorms and at night laying on the damp ground but with one thin blanket to cover with. I say imagine you see us in this fix and you will have a slight idea how we soldiers have to live. But this war will not last always. I look forward for better to come. I often sing that good old song, “There is a better day a coming.” I don’t mind the hardships much for I know I am in a good cause for I believe our cause is the cause of God. We are only ministers of his justice.”

William Clemmons Gets the Mumps

Battle wasn’t the only danger soldiers faced in the Civil War. Sickness and disease were also rampant and William Clemmons soon fell victim. On September 8, 1861, he wrote to Sarah Jane to update her about his regiment as well as his own condition.

“I am not exactly well at this time. I have got the mumps. I think though I will be well in a few days. Our Regiment was ordered out on picket last Tuesday about 12 miles from here. I went but took the mumps and had to come back to the camp the next morning. We went [with]in one half of a mile of the Yankees. They were on one mountain and we on another in plain view of each other. They appeared to be very impudent and it seemed by their actions that they wanted us to attack them. Our regiment was sent there to relieve a North Carolina regiment. Our regiment stayed there until Friday when they were relieved by the 14th Regiment of Tennessee. There is a standing guard kept there all the time. We will attack the enemy in a few days—(i. e.) it is thought so by the officers. Our regiment has moved 4 miles further. On being sick, I have not moved yet. I guess I will go in the morning.”

By late October, 1861, William Clemmons had recovered and wrote to Sarah Jane. He detailed the difficult passage over Cheat Mountain and the battle that occurred there. While some of his regiment got into a skirmish there, he was not personally involved in any of the fighting.

“We have had some hard marches since then, I can assure you. The first was our march to Cheat Pass where we were in the midst of Yankees. I cannot describe the road we had to travel; in fact, a great portion of the way, we had no roads at all. We traveled over mountains the steepest I nearly ever saw. Perhaps some places where no human being ever went before. We were on that trip about six days. Cooked up provisions before we started for four days so we where without anything to eat for two days with the exception of what little we cooked. Had no fire. Rained most of the time and pretty cold too. We had no fight at least. Our regiment—some of the pickets—got into a skirmish and one of our regiment got killed belonging to [Capt. James] Baber’s company [C]. Col. Maney’s [1st Tennessee] regiment was fired at by the Yankees. Some two or three of his men were killed and about the same number wounded. Col. Maney’s men returned the fire. It is not known how many of the enemy were killed.

We took some seventy odd prisoners in all of that. I can assure you, the balls from the enemy guns whistled over our heads while the firing was going on. We could not see them though some of us would be gathering blackberries at the same time and all seemed keen to get into a fight. You have heard no doubt several times that we had been into a fight. Well, we were not into the fight but did come very near being in one.”

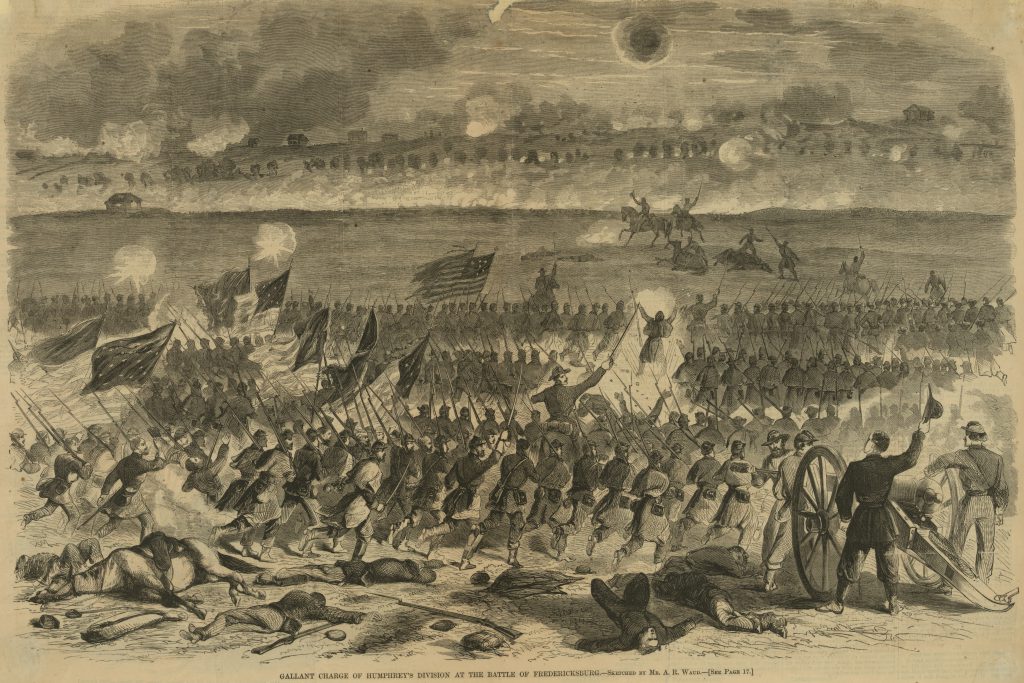

Christmas at Fredericksburg

William Clemmons final letter in our Research Arsenal Collection was written over a year later, on December 31, 1862. In contrast to his early letters full of excitement and optimism, his tone in this letter was very somber, colored by his recent experience in battle.

“We have had a very hard fight near Fredericksburg the 13th of December and I reckon you have heard of it before now. James Tate got killed. I shot 44 rounds at them. I am confident that I killed some of them.

As for the army, I can’t say anything about the movements of it. All things are still and quiet. We are not looking for another fight soon. It is now Christmas so the boys call it but all things looks so gloomy that I cannot enjoy. I had one dram Christmas morning. That was the first I have had since I left home. Christmas has played out until this war stops and when we get home, times will be like they was in old days.”

On April 2, 1865, William Clemmons was captured at Petersburg and imprisoned at Lookout Point, Maryland. He was released on June 24, 1865 and returned home. He married Sarah Jane Bettes and together they had a son, William Edwin Clemmons, Jr. William Clemmons’ health never recovered from the strains of the war and he died on April 13, 1867.

We’d like to give a special thanks to William Griffing of Spared & Shared for his work in sharing and transcribing these letters.

To read more of William Clemmons’ letters as well as thousands of other Civil War letters and documents, sign up for a Research Arsenal membership.

If you enjoyed this article, check out some of our other featured collections like Henry Markham of the 2nd Illinois Cavalry and Charles Miller of the 140th New York Infantry.